WHAT IF?

“In war great events are the results of small causes.”

Julius Caesar

Bellum Gallicum

History is replete with examples of Caesar’s observation. Concerned about German progress in nuclear energy research, the physicist Leo Szilard urged his friend Albert Einstein to use his prestige to alert the American government to the very real danger of an atomic weapon in fascist hands. Albert Einstein complied with a short letter to President Roosevelt dated 02 August 1939. President Roosevelt approved what became the Manhattan project on 06 December 1941. The next day Japan struck Pearl Harbor. Six years after Einstein’s note two American atomic bombs ended World War II.

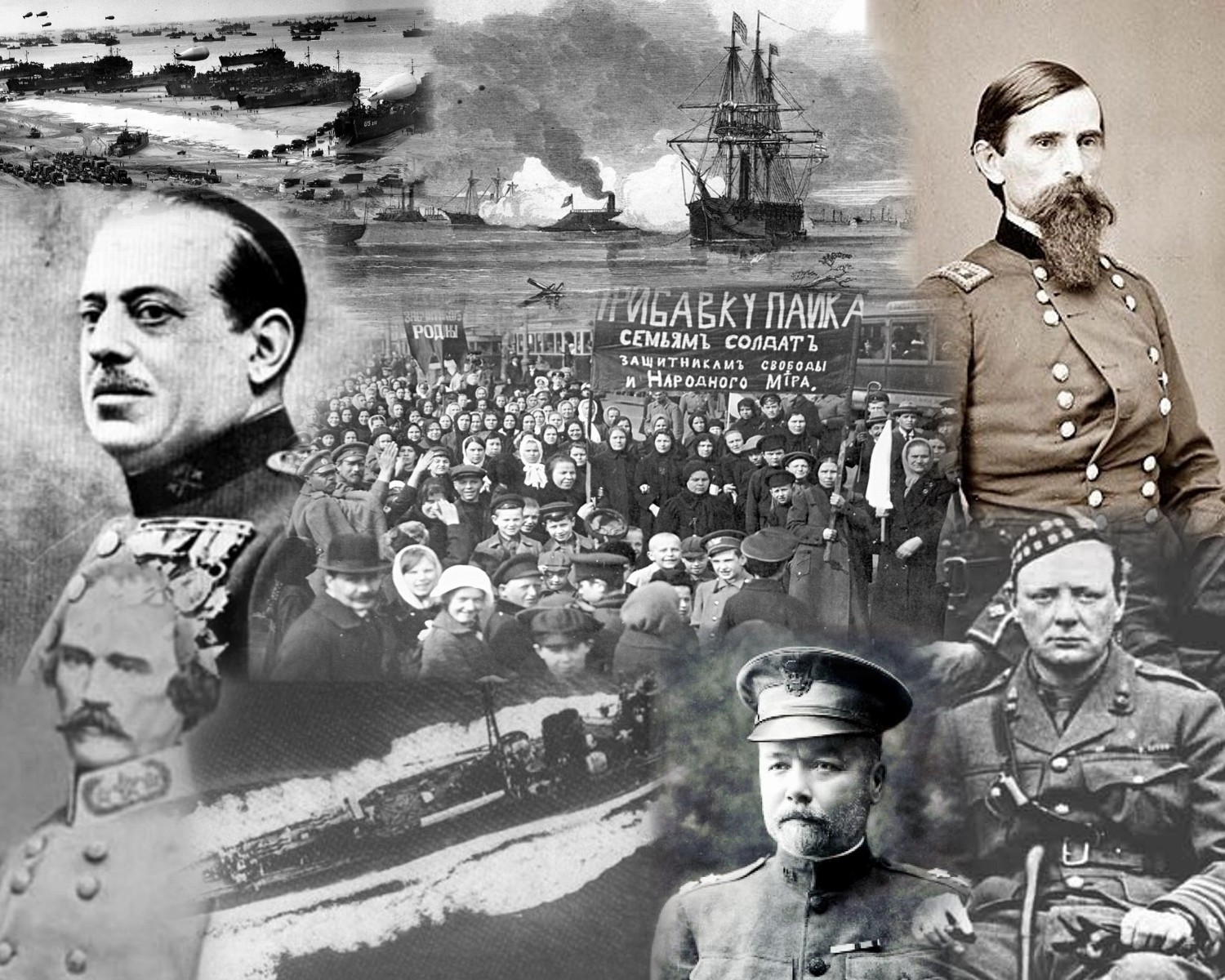

By the same token small changes could result in equally great and completely different events – the ‘what if’ scenario that makes history so fascinating! On 13 September 1862 soldiers of the 27th Indiana found three cigars wrapped in a copy of General Lee’s Order Number 191 written and dispatched on the ninth. Intended for General D. H. Hill but intercepted by Union soldiers when the package was carelessly lost, this windfall gave General McClellan the opportunity but not the audacity or skill to destroy the Army of Northern Virginia at Sharpsburg ending the Civil War in the fall of 1862. Instead, the increasingly bloody conflict continued for another three years. What follows are further examples of small causes that could have had a huge impact on the great events we know as history.

My Kingdom for a (decent) horse

While inspecting General Banks’ army at Carrollton 04 September 1863, General Grant was given a large, nervous horse to ride for the pass in review ceremony. In his Personal Memoirs Grant recounts, “The horse I rode was vicious and but little used, and on my return to New Orleans ran away and, shying at a locomotive, fell, probably on me.” Grant lay insensible in a nearby hotel for over a week and was on crutches for two months afterward. Imagine the American Civil War fought without Ulysses S. Grant, thrown from his horse and killed two months after the fall of Vicksburg. Other than General Sherman, could President Lincoln have found anyone with the innate tenacity, tactical skill and strategic insight to defeat Lee?

The Anarchist and the Bull Moose

Consider the case of Premier Canovas of Spain, a strong man whose policies might have suppressed the growing insurrection in Cuba. Assassinated in 1897 by Miguel Angiolillo, an obscure Italian anarchist long since forgotten by history, the Cuban rebellion escalated into the Spanish-American war one year later. San Juan Hill launched the career of Teddy Roosevelt, who succeeded to the Presidency when yet another anarchist assassinated William McKinley. No Miguel Angiolillo, no Spanish-American war, no San Juan Hill, no Teddy Roosevelt Presidency, no Bull Moose Party to split the Republican Party and, consequently, Woodrow Wilson loses to Taft in 1912, altering the course of World War I.

The Big Apple and the Fate of England

In December 1931 New York City was a most ungracious and inhospitable host to a distinguished visitor from England. Attempting to cross a busy street and forgetting the rules of the road were reversed in the colonies, he looked in the wrong direction before stepping off the curb and was struck by a taxicab traveling north on Fifth Avenue. While under treatment at Lenox Hill Hospital for a badly gashed forehead, cracked ribs, numerous deep bruises and a crushed right foot the former Member of Parliament, Home Secretary, First Lord of the Admiralty, Chancellor of the Exchequer and noted author developed Pleurisy. Had he died could anyone other than Winston Churchill have lead England to her finest hour nine years later?

Timing is Everything

On 07 December 1941 an Imperial Japanese Navy Task Force consisting of six fleet carriers,[1] two battleships,[2] two heavy cruisers, one light cruiser and nine destroyers commanded by Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo struck Pearl Harbor, devastating the American battleship fleet. At a cost of nine fighters, fifteen dive bombers and five torpedo bombers the Japanese sank the Arizona, California, Utah, Oklahoma and West Virginia and badly damaged the Maryland, Nevada, Pennsylvania and Tennessee, as well as destroying or damaging over three hundred military aircraft stationed on Oahu. Fortunately the Enterprise, Lexington and Saratoga were underway at the time of the attack along with thirteen, in this instance, lucky cruisers and escorting destroyers.[3] On 17 December Vice Admiral William S. Pye temporarily relieved the disgraced Admiral Husband E. Kimmel.[4] With orders from President Roosevelt to, “get the hell out to Pearl and stay there until the war is won”[5] Admiral Chester W. Nimitz took command of the shattered Pacific Fleet two weeks later.

In January 1941 President Roosevelt had offered Admiral Nimitz the job of Commander in Chief Pacific Fleet (CINCPACFLT), bypassing many senior officers. Considering the negative effects this might have Nimitz declined and the position went to the ill-fated Admiral Husband E. Kimmel. Had he accepted Nimitz would have fallen in disgrace on 07 December. Roosevelt and King would have been hard pressed to find anyone as capable as Nimitz, who could have counterbalanced MacArthur, managed the egos of Admiral Halsey and General Holland Smith, and co-ordinated the operations of thousands of ships and planes while simultaneously directing the dual advance which brought the war in the Pacific to a successful conclusion.

An airplane fails, an Empire falls

The Japanese were quick to exploit their tactical success at Pearl Harbor. Malaya, Hong Kong, the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies and Burma rapidly fell to combined army and navy forces in a Japanese blitzkrieg. At this point most Japanese admirals argued for a concerted push toward Port Moresby, Papua to complete the conquest of New Guinea, combined with a continued drive to Tulagi in the Solomon Islands to seize control of the Coral Sea region. Control of these critical areas would isolate Australia and quite possibly lure the remnants of the American navy to its destruction, leaving Hawaii, Midway and the Aleutian Islands vulnerable.

On 18 April 1942 American audacity changed everything. The Doolittle raid on Tokyo humiliated the Imperial Army and Navy causing grave loss of face. While tactically insignificant, those sixteen B-25 twin-engined bombers flown from the aptly named carrier Hornet stung the Japanese psyche and, radically altering Japanese strategy, focused complete attention on Midway, the perceived weak link in the Empire’s defensive perimeter.

Overriding all opposition with his tremendous prestige, Admiral Yamamoto pushed forward a convoluted plan calculated to finish the destruction of the American fleet begun at Pearl Harbor. Practically every unit in the Imperial surface fleet (sixteen submarines, seven aircraft carriers, eleven battleships, ten cruisers, sixty destroyers, eighteen troop transports, five seaplane carriers and four minesweepers) played a part in Yamamoto’s master stratagem. Designed to deceive and confuse the Americans, luring her carriers into an enormous trap, Yamamoto’s plan took into account every contingency except American capabilities and intentions and the element of chance, what Clausewitz called the “friction” of war and others term the fortunes of war. The primary objective, destruction of the American carriers, got lost as the grandiose scheme evolved. Disregarding the basic principles of war, Yamamoto divided his enormous fleet into five separate forces. The Midway Occupation Force was further subdivided into five distinct groups. Sailing independently, none of these forces could support the others. J. F. C. Fuller aptly describes Yamamoto’s strategic concept with this analysis, “This plan was radically unsound and the distribution of forces was deplorable. Both were complex; the aim was confused and the principle of concentration ignored.”

Even so – even taking into account the intelligence gathered through cryptographic analysis – Yamamoto’s Carrier Striking Force consisting of four aircraft carriers, two battleships, two cruisers and twelve destroyers under the command of Admiral Nagumo should have been more than a match for the American fleet lurking northwest of Midway. The United States could muster only three carriers, seven cruisers and fourteen destroyers for this crucial battle.

At 0430 on 04 June 1942 Nagumo’s Carrier Striking Force turned into the wind, launching the first wave of fighters and bombers against Midway. Search planes from the carriers Akagi and Kaga as well as seaplanes from the battleship Haruna and the heavy cruisers Tone and Chikuma immediately followed, seeking the American fleet. Completed in 1938 and 1939 respectively, Tone and Chikuma were Japan’s latest, most modern cruiser design. Measuring 650 X 61 X 21 feet and displacing 15,200 tons, they carried eight 8-inch guns in four turrets forward, eight 5-inch guns in secondary batteries amidships, up to fifty-seven 25mm antiaircraft guns and twelve 24-inch torpedo tubes. Purpose-built for scouting operations, the after decks were fitted catapults, cranes and facilities for five seaplanes. Ideal reconnaissance platforms, Tone and Chikuma were given the center lanes of the planned search pattern.

As it had at Pearl Harbor, however, fate intervened once again. The catapult aboard Tone malfunctioned, delaying the launch of its aircraft until 0500. Engine trouble also prevented the Chikuma from launching her seaplane as scheduled. Its flight path would have taken it directly over the American carriers a scant 215 miles away, but further engine trouble caused it to turn back early. Consequently it was not until 0820 that Nagumo received confirmation of the presence and location of the American carriers from Tone’s aircraft. By then it was too late. American torpedo planes and dive-bombers were already inbound.

Although the American torpedo planes were ineffective, their heroic attack prevented the Japanese carriers from launching additional planes and drew the fighter cover down to sea level, setting up the Akagi, Kaga, Soryu and Hiryu for the follow-on dive bombers. Decks crowded with planes, fuel and ordnance, the pride of the Imperial Fleet were soon flaming wrecks. 300 miles astern with the main body consisting of three battleships, one carrier, two seaplane carriers and twelve destroyers, Yamamoto could do nothing to avert disaster.

In exchange for the carrier Yorktown and the destroyer Hammann, American forces sank all four carriers of Nagumo’s Striking Force as well as the heavy cruiser Mikuma. Badly damaged, the cruiser Mogami spent the next year in Truk undergoing repairs. More importantly, the Japanese lost their best naval pilots and most experienced aircrews. This was a loss from which they would never recover. Midway ended the Japanese threat to Hawaii and Australia. The initiative in the Pacific now passed to the Allies and was never seriously challenged again.

Had Chikuma’s aircraft launched as scheduled, Admiral Nagumo might have finished what he began at Pearl Harbor, radically altering the course of World War II.[6]

Keep your enemies close and your friends closer

Ironically American involvement in Vietnam began in 1945 when an OSS (Office of Strategic Services, forerunner of the CIA) team parachuted into the jungles of Vietnam. There they found Ho Chi Minh in a remote camp deathly ill with malaria. After nursing him back to health and providing him with supplies, his guerilla forces were unleashed upon the Japanese to prevent their transfer to more active sectors of the Pacific. After Japan’s surrender Vietnam was divided along the 17th parallel. Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Minh took control of North Vietnam, while French colonial rule was restored in the South. Predictably peace in Southeast Asia was short lived. By December 1946 open war broke out between the French and the Viet Minh.

On 03 December 1950 thirty-five Americans arrived in Saigon to establish the Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG). United States’ support for France rapidly grew and American involvement continued even after the French debacle at Dien Bien Phu 07 May 1954. Six months later President Eisenhower pledged ongoing support for South Vietnam in its struggle against Communism. In February 1961 President Kennedy greatly extended this policy by sending combat advisors to South Vietnam and establishing the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) in Saigon commanded by General Westmoreland. From these modest beginnings American involvement rapidly escalated and the build up of troops followed apace peaking at 650,000 in 1969.

On 02 August 1964 North Vietnamese patrol boats attacked the destroyers USS Maddox and USS Turner Joy with an alleged second attack two days later sparking the Gulf of Tonkin Incident.[7] On 07 August 1964 President Johnson sought and received a virtual blank check from a willing congress to wage war in Vietnam.

On 06 April 1965 President Johnson authorized United States forces to seek out and engage the enemy in combat, a radical departure from their former ‘advisory’ role. At the same time he offered an extensive aid package to North Vietnam in exchange for a peaceful settlement with South Vietnam. Much to his astonishment, his offer was scornfully dismissed.[8] The rest as they say is history, albeit a tragic history.

Conclusion

In war great events are indeed the result of small causes. The future may hinge on a temperamental horse or a speeding cab. The slightest change in those small causes potentially alters what we know as history.

* * *

Footnotes

[1]. Akagi, Kaga, Hiryu, Soryu, Shokaku and Zuikaku .

[2]. Hiei and Kirishima .

[3]. Enterprise was delivering aircraft and supplies to the doomed garrison on Wake Island. Lexington was on a similar mission to Midway. Just completing overhaul Saratoga was moored at San Diego.

[4]. Rightly or wrongly blamed for the Pearl Harbor disaster the public associated his name with negligence, incompetence and utter failure. His position irretrievably compromised Kimmel could not continue as CINCPACFLT.

[5]. E. B. Potter, Nimitz (Annapolis, MD, 1976), 9.

[6]. The unlucky Chickuma was crippled by aircraft from Task Force 77.4.2 North East of Samar and was scuttled by torpedoes from the destroyer Nowake on 25 October 1944. Given command of naval forces in the Marianas in March 1944, in the final stages of the battle for Saipan Admiral Nagumo committed suicide rather than surrender.

[7]. Officially the destroyers were on “routine patrol”. In reality there were engaged in an aggressive intelligence-gathering mission supporting coordinated attacks upon North Vietnam by the South Vietnamese navy and the Laotian air force. The North Vietnamese may have inadvertently attacked the Maddox, mistaking it for a South Vietnamese vessel on 02 August. The second attack on August 4th has since been attributed to freak weather conditions, unconfirmed sensor reports and strained nerves.

[8]. One of the most effective legislators in American history and a consummate politician Johnson could not understand why Ho Chi Minh could not be bought with a generous aid package as he had bought so many others during his career.