Prologue:

In his war commentary, Bellum Gallicum, Julius Caesar wrote, “In war great events are the results of small causes.” History is replete with examples of this dictum; stirring sagas of courage under fire; gallant stands by a handful of men against overwhelming odds; small battles that disproportionally influenced the outcome of major wars; epic chronicles that inspire us to this day.

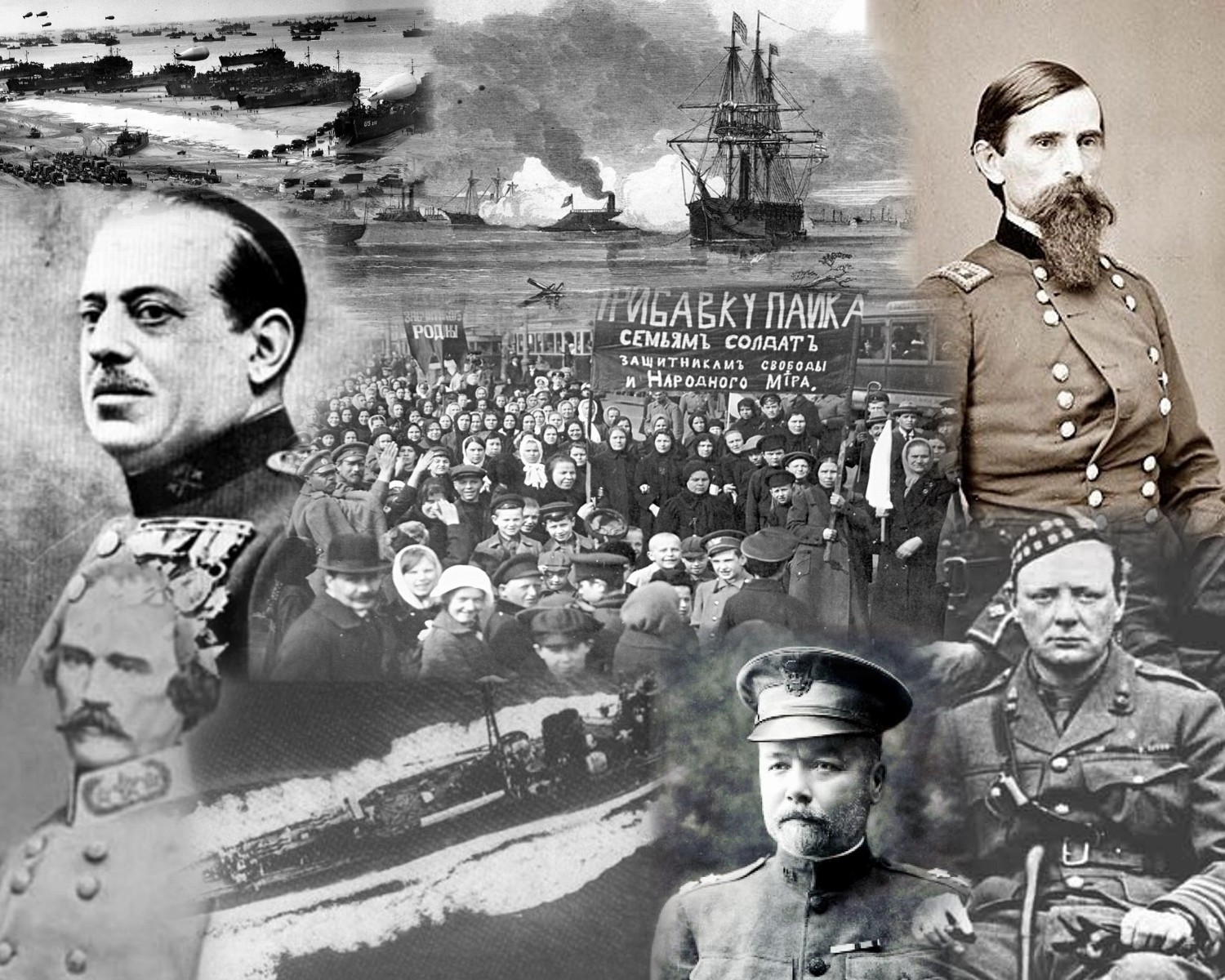

In 480 B. C. Xerxes led a Persian host estimated at 200,000 against the Greek city-states. The upstart Greeks were fomenting trouble in Ionia with their radical ideas regarding democracy, ideas the all-powerful autocrat despised. Knowing they could not match Persian numbers in open battle the Hellenes abandoned northern Greece choosing instead to make a stand at Thermopylae. At the middle gate the defile along the coastal plain spans a mere fourteen feet. At this perfect defensive point superior Greek arms, armor and tactics negated Persian numbers. For three days Leonidas, King of the Spartans, with 7000 hoplites mustered from the various Greek city-states stood firm. Then a traitor revealed a little used mountain track around their position to the enemy. Outflanked by the Immortals, Xerxes elite infantry, many Greek contingents fled. Spurning surrender Leonidas and his Spartans fought to the death buying precious time for their countrymen to prepare. Despite their sacrifice at Thermopylae, Athens was lost. When combined with the subsequent naval victory at Salamis however, Greece was saved.

In 1854 French, British and Turkish forces invested Sevastopol. On 25 October Prince Alexander Sergeievich Menshikov attempted to lift the allied siege. After a three hour preliminary bombardment Russian infantry charged and carried a Turkish redoubt. Russian heavy cavalry poured through the broken line and raced for Balaklava the British supply base. In a bloody clash the remnants of retreating Turkish forces and the ‘Thin Red Line’ of the famous 93rd Highlanders threw the Russian Cuirassiers back.

In the context of valiant struggles against long odds the Battle of the Alamo, Rorke’s Drift and the RAF during the Battle of Britain also come to mind. In that vein, this article will address the lesser known but equally deserving Battle of the Kokoda Trail which saved Australia and profoundly influenced the War in the Pacific.

Introduction:

The editors of Life magazine could not be accused of sensationalism for their 02 March 1942 cover page banner headline, NOW THE U. S. MUST FIGHT FOR ITS LIFE. In the spring of 1942 Allied prospects were indeed grim. Rommel was on the offensive in North Africa. In Europe the Wehrmacht survived the debacle at Moscow, blunted the Russian winter counter attack and would shortly launch campaigns in the Balkans and the Caucasus. The Japanese blitzkrieg continued unabated in Burma, China, the Dutch East Indies, French Indo-China, Malaya and the Philippines. Feature articles pondered Japanese invasions of Australia, Hawaii, even the United States. With only 100,000 hastily mustered, poorly trained, ill-equipped and inadequately supplied troops to defend the entire Pacific coast these stories were not as farfetched then as they appear now.

If America was unready, then Australia was even less prepared. Her best units were fighting with the British 8th Army or languishing in Japanese POW camps after the fall of Singapore. Protection by the Royal Navy sank with HMS Repulse and HMS Prince of Wales. With the remainder of the fleet fighting for England’s survival in the Atlantic no additional ships could be spared for the Pacific.

During World War II airfields drove strategic decisions in the Pacific. Land based air power projected sea control / sea denial capabilities out 300 miles or more. If Imperial Forces captured the airstrips around Port Moresby, New Guinea isolation of Australia was probable; invasion of Queensland quite possible. In either case damage to the Allied cause might be irrevocable. The naval battle of Coral Sea (3 – 8 May) ended the sea borne threat to Port Moresby. Well aware of New Guinea’s strategic significance, on 21 July 1942 the Japanese countered by landing 11,000 troops at Buna and Gona on New Guinea’s northern coast. With 6000 troops Major General Tomitaro Horii immediately pushed inland along the Kokoda Trail toward Port Moresby 130 miles south. It was now a race against time for both the Australians and the Japanese. Thousands would fight and die in some of the worst terrain imaginable along the Kokoda Trail, the narrow track that crosses the Owen Stanley Range linking Gona and Port Moresby.

New Guinea:

The world’s second largest island, New Guinea is geologically young with volcanic peaks reaching 16,000 feet. The Owen Stanley Range divides the island North and South. Numerous streams and rivers further split the island East and West. Located just eleven degrees below the equator, constantly inundated with heavy rainfall, covered with dense vegetation, most of New Guinea is a hot, humid, equatorial jungle. Violent rains dump up to an inch of water in five minutes. Rivers rise as much as nine inches per hour. Yet at altitude trekkers suffer from hypothermia brought about by sudden hailstorms. To call New Guinea inhospitable is an egregious understatement. It is a primordial world, like something penned by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle or Jules Verne. Not even the discovery of gold in the 1930’s could tame New Guinea. As James Bradley writes in The Boys Saved Australia, “a road just seventy miles long was deemed impossible to build and planes had to ferry supplies in and ore out.”

To reach their objective the Japanese first had to traverse the formidable Owen Stanley Range via the Kokoda Trail. Trail implies a peaceful, winding path. The Kokoda Trail is nothing of the sort. A dangerous, narrow track hacked out of the jungle and carved out of the mountains, it crosses the Owen Stanley Range at 7000 feet via a series of twisting switchbacks and rough-hewn steps cut into steep slopes. Prior to the war it was considered passable only by natives and provincial officers. The optimistic figure of 130 air miles from Gona to Port Moresby held a far different reality on the ground where exhausted soldiers struggled first through dense jungle followed by a backbreaking climb. As if thick rain forests, rugged mountains, swift, treacherous streams and muddy, precipitous drops were not daunting enough obstacles in themselves a plethora of poisonous insects, dangerous wildlife, tropical diseases and cannibalistic headhunters awaited those who strayed too far from the beaten path.

Australian versus Japanese Forces:

To counter the Japanese threat Australia rushed a militia unit, the AMF 39th Battalion, up the Kokoda Trail. Clad in Khaki uniforms appropriate for desert conditions but completely unsuited for jungle warfare, shod in leather boots which soon rotted away, equipped with World War I vintage Enfield rifles the Aussies were supported by nothing heavier than light mortars and Bren and Lewis machine guns. Further the 39th had just completed basic training, had no combat and certainly no jungle experience.

In contrast Major General Horii’s command, designated the South Seas Detachment (Nankai Shitai), was comprised of elite troops, veterans of earlier campaigns. Clothed in green camouflage uniforms, shod in functional jungle boots they carried little food (hoping to live off the land and captured supplies) but large quantities of ammunition. They also carried heavy mortars, heavy machine guns and even mountain artillery for support.

For the Japanese success depended upon speed. They must cross the Owen Stanley Range capturing Port Moresby before Allied reinforcements arrived in substantial numbers. Once in Japanese hands its airfields would ferry in the troops, supplies and equipment necessary for further operations. Foregoing provisions for mobility Horii counted on Yamato Damashii (Japanese Spirit) and overwhelming firepower to carry the day. Pushing forward relentlessly, scouts sprinted ahead of the main body sacrificing their lives to flush out and target enemy positions.

For their part the 39th pushed across the Kokoda Trail first halting the Japanese at Wasida 23 – 27 July. Outnumbered and outgunned for sixty days the Aussies conducted a heroic fighting withdrawal, turning to face their determined opponents at Kokoda (28 July), Deniki (29 July – 11 August), Seregina (2 – 5 September), Efogi (8 September), and Menari (16 September). The final confrontation took place at Ioribaiwa 17 – 26 September. At that point the depleted South Seas Detachment held positions within thirty miles of Port Moresby. At night its lights beckoned the weary Japanese. Scourged with malaria, racked with dysentery, weakened by hunger the Japanese could advance no further. On 23 September, two months after the Japanese landings at Buna and Gona, the 7th Australian Division counterattacked. Now it was the Japanese who conducted a bitter fighting withdrawal over the Owen Stanley Range. By November the remnants of Horii’s force were entrenched in the Buna – Gona area. Reinforced by the American 32nd Division Gona fell to Allied forces on 9 December. Buna finally capitulated in January 1943.

The Human Cost:

Fighting in New Guinea was especially gruesome. With so much at stake, rugged terrain, foul climate, tenuous supply lines and the desperation of both combatants magnified the always-brutal nature of close quarters combat.

Provisions were limited to what the soldiers carried and what could be packed in. Ammunition got top priority, food second, hospital supplies third. Consequently medicine was always in short supply, often non-existent. Lacking any other medical care Jim Moir and many other soldiers allowed blowflies to lay eggs in their wounds. The resultant maggots ate their rotten flesh keeping the wound clean and preventing gangrene.

Out of necessity stretcher-bearers were limited to only the most severely wounded. When Japanese machinegun fire shattered his lower leg medics fabricated a splint out of banana leaves. Refusing a litter, Charles Metson wrapped his hands and knees in rags and crawled down the trail he had so laboriously climbed just days before. Such was the spirit and the fortitude of the 39th Battalion.

Aftermath:

The Supreme Commander, Allied Forces, Southwest Pacific never visited the front, ignored reports on conditions and dismissed intelligence estimates on Japanese strength. Far removed from the desperate fighting, comfortably housed and safely ensconced at their Brisbane Headquarters “Dugout Doug” and his “Bataan Bunch” (as the Aussies derisively labeled MacArthur and his staff) railed against the Australians, first over their continuous retreat, then for the time-consuming counter offensive. In a dispatch to Washington MacArthur cabled, “The Australians lack fighting spirit.” MacArthur further damaged relations when he signaled, “Operation reports show that progress on the trail is not repeat not satisfactory.” Given an undeservedly deficient reputation by the refugees from the Philippines, Australian units were relegated to secondary fronts for the remainder of the war.

MacArthur’s questionable opinion does not bear close scrutiny. Fighting horrendous conditions as well as the Japanese the Australians gave Japan its first defeat on land. The significance of that achievement cannot be overstated for a Japanese victory in New Guinea changes the entire strategic picture of World War II in the Pacific. Japanese planes based in Port Moresby could have interdicted Allied supply lines isolating Australia. To ensure she remained in the war, troops earmarked for the Solomons would have been diverted, postponing the invasion of Guadalcanal for six months or a year. Given additional time to dig in the inevitable Allied counterattack becomes even more costly.

The battles described in the prologue were not chosen randomly. The naval victory at Salamis overshadowed the deadly confrontation at Thermopylae just as the naval engagement at Midway eclipsed the battle of the Kokoda Trail. Even though they fought courageously in the Crimean War the Turks were vilified by Lord Raglan (covering his own desultory performance and deadly tactical mistakes) and used as human pack animals for the remainder of the conflict. So too, MacArthur used the Australians badly, maligning them publicly, giving them subordinate roles in inconsequential areas for the balance of World War II.

Never the less if Midway was the turning point for the United States, then New Guinea was the defining moment for Australia. Although comparatively few troops were engaged their spirit was unmatched and the battle of the Kokoda Trail greatly influenced the outcome of the Pacific War. On 29 August of each year Australians rightfully observe ‘Kokoda Day’ to honor the young men who endured so much.

Postscript:

“Good people sleep peaceably in their beds at night only because rough men stand ready to do violence on their behalf.”

George Orwell

Those who have forgotten the lessons of 11 September 2001 and choose to ignore the dangers terrorism continues to pose (not to mention China, Iran, North Korea and Russia) would do well to heed those words. During the American Revolution approximately three per cent of the colonists bore arms against the English, pledging their lives, their fortunes and their sacred honor for freedom. Today those precious few men and women serving in distant lands, confronting the forces of terror, preserving the freedoms others take for granted, numbers less than one per cent. By their actions they preserve and carry forward the legacy of Thermopylae, Balaklava and Kokoda – service, sacrifice and an impact far greater than mere numbers would suggest; an influence not yet fully understood or appreciated.