Introduction

History seems fixed; a series of dates and events recorded in dusty tomes, such as the voyage of Columbus in 1492, leading to the colonization of the New World, war between the great powers of the time – Spain, France and England – revolution, independence and so on, one incident following another as links in a causal chain, resulting in the inevitable present. It is not! In his treatise on the fall of the Soviet Union, entitled 1989 WITHOUT GORBACHEV, respected historian Mark Almond writes:

“The collapse of Communism is now history. Already it seems inevitable. But it is worth remembering that no major event in modern history was less predicted by the experts than the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 or the hauling down of the red flag for the last time from the Kremlin in 1991. The rubble left behind by great revolutions and the collapse of great empires is always impressive and its very scale makes it tempting to look for fundamental, long-term causes. However, looking for the deep roots of historical change is the deformation professionelle of historians. Sometimes what happened did not have to be; or to put it another way, it only became inevitable very late in the day.”

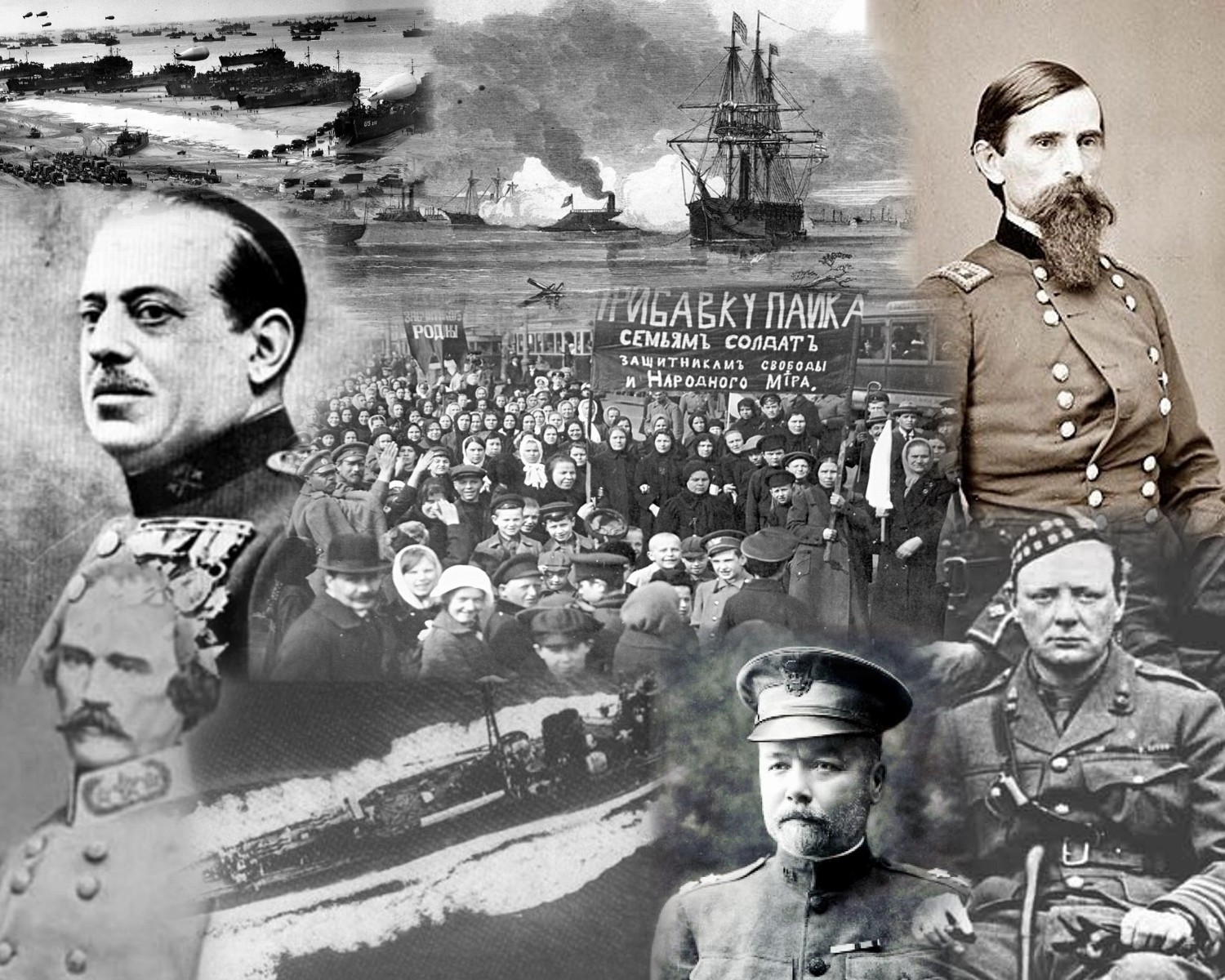

Indeed the chronicle of mankind is quite malleable, the outcome of occurrences as great as World War II and as small as the virus that caused the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918. History is the result of myriad interconnected cultural, economic, political, religious, scientific, social and technological factors. Integral to this mixture is the role of men and women who are either born to greatness or, in most cases, have greatness thrust upon them. Remove those people through accident or disease and the outcome of what went before, what we call history, becomes quite different. Much of history also falls into the province of chance and the realm of unintended consequences. Consider Alfred Nobel. Grievously underestimating mankind’s capacity for self-destruction, Nobel believed his invention of dynamite would usher in an age of peace for warfare would become too horrible for any civilized nation to contemplate. In the same manner the revolution in transportation that began with the domestication of the horse, and culminated centuries later in the development of the train and the automobile, both intended to replace the horse, have had a far greater impact upon the course of human events than anyone could have imagined. The crossroads where horses, iron horses, horseless carriages and the movers and shakers of recorded history meet is a remarkable junction abounding with opportunities for fascinating detours.

The Iron Horse

For good or ill few machines developed during the Industrial Revolution have had greater impact on history than the railroad. Trains moved the army of Brigadier General Joseph E. Johnston from the Shenandoah Valley to Manassas Junction in time to turn the tide of battle in the first great clash of the American Civil War. In that battle the First Brigade of Virginians and its commander, an eccentric former instructor at the Virginia Military Institute, General Thomas J. Jackson, earned the sobriquet “Stonewall.” Given a Union victory at Manassas / Bull Run the Civil War would have ended in 1861. A Confederate victory set in motion the deadliest war in United States History. Following four years of internecine warfare the Iron Horse opened the North American continent from the Atlantic to the Pacific to mass migration, exploitation and industrialization.

The events of August 1914 presented Kaiser Wilhelm II with several poor choices; among them: ignore the plight of his ally, Austria-Hungary, Drang Nacht Osten or implementation of the Schlieffen Plan. In that era the first was unthinkable. The second had much to commend it for war in the east would give England and France no causus belli to enter the war. Unfortunately for millions of soldiers strict adherence railroad schedules which, in turn, dictated mobilization schedules, precipitated yet another four year bloodbath between the Great Powers of Europe. Of all the events, great and small, associated with trains however, perhaps the most significant occurred not at the beginning but during the course of the War to End All Wars.

1916 was the year of great battles – Verdun, Isonzo, Jutland, Somme and the Brusilov offensive. Millions of lives were exchanged for a few square miles of shell cratered, blood soaked earth and the net result of that tremendous sacrifice was continued stalemate. By year’s end the Central Powers faced three new enemies – Italy, Romania and Portugal; one fearsome new weapon – the tank; and slow strangulation by air raids and naval blockade which were devastating their ability to wage war and maintain morale. American entry into the war was a matter of when rather than if due to German U-Boat activity however the U-Boats were Germany’s only counter to British naval supremacy. Caught on the horns of this strategic dilemma Kaiser Wilhelm II and his Imperial General Staff were desperate for any solution that might break the impasse. Fatefully an initiative begun in February 1915 began to bear fruit at this time.

Israel Lazarevich Gelfand was a Russian revolutionary who took the nom de guerre “Parvus” (the little one). Fleeing from the Okhrana, Czarist Russian secret police, he made his way to Germany in 1891 where he wrote for various left wing newspapers and met with fellow exiles Kautsky, Lenin, Luxemburg and Trotsky. After Bloody Sunday on 22 January 1905 Gelfand returned to Russia fomenting revolution. Imprisoned in Siberia he managed to escape, making his way to Turkey. For a dedicated communist he proved quite adept at capitalism. Forging a business empire in Constantinople he became very wealthy. Gelfand even owned a bank. These business activities served as a legitimate front for his true calling – war profiteer – selling weapons, cognac, caviar, cloth, etc., to anyone and everyone who could meet his price. Near continual war in the Balkans at this time created a plentiful supply of patrons and near limitless proceeds. Gelfand never lost his revolutionary fervor however. When the turmoil of the Balkans engulfed the Great Powers in August 1914 Gelfand saw an opportunity to advance the communist cause. Gelfand first approached the German Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire with a detailed plan to topple the Czar. Intrigued the Ambassador referred him to the Foreign Office in Berlin where he was received in February 1915. There he laid out an operation based on subversion and sabotage culminating in a coup. Guided by the principle, “The enemy of my enemy is my friend,” Germany allocated two million Deutsche Marks to support revolutionary propaganda in Russia. Coordinated by the German Ambassador in Copenhagen, Count Ulrich von Brockdorff-Rantzau, “propaganda” in the form of weapons and dynamite were smuggled through Sweden into Finland, then a Grand Duchy within the Russian Empire.

The February Revolution of 1917 toppled the Czar and established a provisional government. To the Kaiser’s chagrin however, Russia staggered on, her armies remaining in the fight. At that point Germany took more direct action. On 09 April 1917 thirty-two Russian exiles, among them Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, better known to history as Lenin, left Zurich on a chartered train provided by the Kaiser. No train has ever carried a more dangerous passenger. One week later they reached Petrograd and set to work fomenting insurrection culminating in the October Revolution of 1917. In the long term the October Revolution precipitated a civil war which ended with Lenin firmly in control of a communist dictatorship. That civil war and the Allied Entente involvement on behalf of the White Armies shaped the nature and the world view of the USSR until its fall in 1991. Although she would not formally withdraw until the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, in the short term the October Revolution of 1917 effectively ended Russian involvement in World War I. Lenin saw this action as a necessary step in the consolidation of power. The Allies viewed this decision as an act of betrayal. In either case Russian capitulation allowed Germany to transfer seventy divisions to the Western Front where she hoped to wage the final, decisive battles of the Great War. The Kaiserschlacht failed to break the British or the French; worse the Kriegsmarine had failed to stop the US convoys and the American buildup was underway. After first contact with American soldiers and marines Chateau Thierry, Germany was doomed.

German participation in the Russian Revolution did nothing to change the outcome of World War I and, ironically, that covert operation sowed the seeds of her utter ruin in World War II. For Germany, seldom, if ever, in the annals of human history has such a venture paid so little in return in the short term or proved such an unmitigated disaster in the long term. Reckless disregard of consequences directly impacted global events from 1918 until 1991. Millions suffered and died as a result of expediency. The consequences of that decision continue to this day as Russia attempts to regain her place on the global stage.

The Horseless Carriage

Just as trains have influenced world events, automobiles have also had a storied place in history far beyond mere conveyance of people and goods. For the wealthy expensive sedans are symbols of status. For the masses vehicles provide unprecedented freedom of movement. National leaders love to be seen in cars. Consequently automobiles figure prominently in the annals of Empire and thereby, lend themselves to many intriguing ventures into alternate history.

Emperor Frederick III, head of the House of Hapsburg, German King (1440-1493), Holy Roman Emperor (1452-1493) and last Emperor receiving an Imperial Coronation at Rome is noted for reuniting the family lands under Hapsburg dominion. His greatest coup however, was the acquisition of Burgundy, the Netherlands and Belgium setting Austria on the course to Empire. To be sure there were numerous setbacks in this process for Frederick was not a particularly strong king. He was however, an astute politician, single minded of purpose and had the good fortune to outlive most of his opponents. Frederick’s guiding principle throughout his long reign is summed up in the initials A. E. I. O. U., which he had inscribed on all his personal possessions as a constant reminder of his ultimate goal and daily affirmation of his final objective. In Latin his dictum read, “Austriae Est Imperare Orbi Universo.” (It is Austria’s destiny to rule the world.) In German the maxim reads, “Alles Erdreich Ist Oesterreich Unterthan.” (The whole world is subject to Austria.)

The fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire began on 28 June 1918 near the Latin Bridge in Sarajevo. Archduke Franz Ferdinand (1) escaped a bombing attack at 10:10 A.M., only to fall victim to a 9MM slug fired from a Belgian Fabrique Nationale model 1910 semi-automatic pistol that same afternoon. En route to the hospital to visit those injured that morning; the Archduke’s driver took a wrong turn. That mistake placed the Archduke and his wife in the path of Gavrilo Princip(2), a Serbian nationalist, as he emerged from hiding after the failed bomb attack. That the Hapsburgs no longer rule anywhere, not even in Austria, is apt commentary on the transient nature of political and military power. Continuing conflicts between Serbian, Croatian and Muslim groups in the Balkans serve notice on the limits of nation building in the former Austria-Hungary (or anywhere for that matter) and the far-reaching effects when Empires fall. How the Hapsburgs and Austria met their demise due to a wrong turn is further testament to Caesar’s dictum, “Great events are the result of small causes.”

In similar manner, December 1931 was not an auspicious month for future leaders with regard to automobiles. In New York City for a lecture tour a famous adventurer, author, politician, soldier and statesman left the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel where he was staying to visit the home of Bernard Baruch on Fifth Avenue. Late in the evening of 13 December 1931, the taxi in which he was riding dropped him off across the street from his intended destination. Accustomed to the traffic patterns in his native England he checked for cars as he normally would and stepped into the roadway. There an automobile driven by Mario Contasino struck him. Travelling between thirty to thirty-five miles per hour the vehicle dragged him several yards before throwing the unwary visitor to the street. Severely injured, but still conscious, the gallant gentleman told the investigating police officer, “I am entirely to blame; it is all my own fault.” Rushed to Lenox Hill Hospital, Doctor Otto Pickhardt treated his patient for a three-inch, “up deep to bone” cut on the forehead, a fractured nose, fractured ribs, shock, and “pleurisy, right, traumatic with hemorrhage.” The accident nearly killed him but it did not break his spirit. On 14 February 1931, he wrote that he had, “broken the back of the lecture tour without feeling any ill effects.” Displaying the pluck that had served and would continue to serve him throughout his life he capitalized on the event with an article in The Daily Mail entitled MY NEW YORK MISADVENTURE published 04 January 1932.

Eleven days after Churchill’s accident Adolph Hitler was injured while riding in a vehicle with General von Epp. They were returning from the wedding of Doctor Joseph Goebbels at Kyritiz when they crashed into another car. Thrown against a window, Hitler, unfortunately, sustained only minor bruises and a broken finger.

February 1933 was not much better. On the 15th newly elected Franklin Roosevelt gave an impromptu speech from the back of an open car in the Bayfront Park area of Miami, Florida. Armed with a .32 caliber pistol Giuseppe Zangara, an impoverished Italian immigrant, fired five or six rounds at Roosevelt. Zangara missed Roosevelt but wounded Chicago mayor Anton Cermak (who was traveling with Roosevelt and later died of peritonitis) and four others who grappled with him after the first shot. His motives were unclear but in the Dade County Courthouse jail Zangara confessed stating, “I have the gun in my hand. I kill kings and presidents first and next all capitalists.” His final statement prior to execution (3) in the electric chair was, “Viva Italia! Goodbye to all poor peoples everywhere! Push the button!” Had Roosevelt been hit and died rather than Cermak would his Vice President, John Garner, been able to lead the United States out of the Depression? Would his eventual successor have supported England via “Lend Lease” through the first two years of World War II or, given the prevalent isolationist sentiment in 1939, remained strictly neutral until 07 December 1941?

At the 1955 Churchill Conference in Boston, Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. addressed the issue in this manner, “Would the next two decades have been the same had the automobile that hit him killed Winston Churchill in 1931, and the bullet that missed him killed Franklin Roosevelt in 1933? Would Neville Chamberlin or Lord Halifax have rallied Britain in 1940? Would Vice President John Garner have produced the New Deal and the Four Freedoms? Suppose in addition that Lenin had died of typhus in Siberia in 1895, and Hitler had been killed on the Western Front in 1916? Would the 20th century have looked the same?” Individuals do make a difference in history. Frequently their mode of transportation is a factor in that difference as well.

Wellesley’s Horse

General Sir Arthur Lord Wellesley (4) is best remembered for his pivotal role commanding Anglo-Allied forces during the Waterloo campaign, the culmination of twenty-eight years of distinguished service to the British Empire. In Wellesley’s opinion however, his hardest fought confrontation and greatest achievement was the Battle of Assaye. It was a close run thing and but for the capricious nature of battle could have terminated the incredible career of the future First Duke of Wellington early on.

On 23 September 1803 then Colonel Wellesley, brevetted to Major General, led a small army (5) of 5000 infantry, 4500 cavalry and 17 guns against a Maratha Confederacy force consisting of approximately ten to twelve thousand French trained infantry, an estimated ten to twenty thousand irregular infantry, somewhere between thirty to forty thousand light cavalry and 100 guns ranging from light artillery pieces to 18 pounder cannons. This action was the result of events that began in 1802. Civil war within the Maratha (in some references Mahratta) Empire, a loose confederation of principalities, led to the defeat of the Peshwa, a position similar to that of Prime Minister, Baji Rao II, its nominal ruler. Rao sought refuge with the East India Company (hereafter EIC) to whom he pledged allegiance in return for assistance in reclaiming his position. Lord Mornington, the Governor General of India, saw in this request an opportunity to remove the final obstacle to English dominance of the sub-continent. Subsequently in March 1803 a small army of approximately 15,000 British and EIC troops commanded by Wellesley advanced on Poona while a smaller force of about 10,000 men commanded by Colonel James Stevenson paralleled the line march protecting his left flank. Poona fell and on 13 May 1803 Baji Rao II was reinstated to power. This action greatly angered Daulat Scindia (also spelled Sindhia) and Ragaoji Bhonsle (in some texts Bhonslar), the Raja of Berar, two of the more powerful rulers of the remaining Maratha principalities, who, forming an alliance, declared war on the upstart British. Eager to wrest control of India from the French, Lord Mornington was happy to oblige.

Wellesley then marched on Ahmednagar. Rather than initiate a time consuming siege Wellesley took the city in a short, violent and bloody escalade setting the tone for the remainder of the campaign. Although costly, the victory gave his men, most of whom were native EIC infantry and cavalry units, added confidence in their leader and themselves and was a profound psychological shock to the Maratha army.

After a series of inconclusive marches and counter-marches in pursuit of an elusive foe, Wellesley and Stevenson met at Budnapoor on 21 September. Believing the enemy to be encamped at Borkardan they devised a plan whereby each element would march in separate columns and converge on Borkardan three days hence. It is a truism of military science that no plan survives first contact with the enemy. Such was the case at Assaye. At about 1300 (1 PM) on 23 September 1803 Wellesley found the Maratha army not at Borkardan but strongly entrenched behind the River Kaitna (also known as the Kailna) guarding the only readily apparent ford.

At first glance it was a formidable position. Running from West to East the River Kaitna and its tributary, the River Juah to the North, form an isthmus of land. The town of Assaye sits on the south bank of the Juah while the villages of Waroor and Peepulgaon are sited on the north and south bank of the Kaitna respectively near the confluence of the two rivers. As stated some ten to twelve thousand French trained, mercenary led infantry loyal to Daulat Scinda (6) and 80 cannon faced south defending the only visible crossing. Another ten to twenty thousand irregular infantry commanded by the Raja of Berar and 20 cannon garrisoned Assaye protecting the Maratha left flank. Thirty to forty thousand loosely organized and lightly armed horsemen known as Pindarries (to call them cavalry would give them too much credit for they were more akin to mounted bandits useful only in raiding defenseless villages and riding down broken armies) covered the Maratha right flank.

Garrisons at Poona and Ahmednagar and the need to leave detachments to guard his extended line of supply had reduced Wellesley’s initial force of 15,000 troops to just 5000 Infantry, 1500 horse, a small contingent of approximately 3000 irregular light cavalry (7) and 17 cannon – eight 12 pounders, two 5.5 inch howitzers and 7 lighter pieces. In spite of the disparity in numbers Wellesley opted for an immediate assault declining even to wait to join forces with Colonel Stevenson whom he assumed would march to the sound of the guns (8).

To cross the Kaitna, advance up its steep banks on the far side and assault a force twice the size of his own much smaller army, would have been not war but murder. Personally leading a small cavalry force, Wellesley sought some way to outflank his opponent. While reconnoitering Wellesley observed the village of Peepulgaon on the south side of the Kaitna and its neighbor Waroor on the opposite bank. Assuming a ford must connect the two villages, although his native guides denied it, Wellesley ordered a closer examination of the area. There he found a quite passable ford did, indeed, exist.

By now it was around 1500 (3 PM), rather late in the day to begin a major engagement especially considering the disparity in numbers. Fearful that the enemy might slip away and counting on British discipline to carry the day Wellesley, without hesitation, ordered his army to cross the river at Peepulgaon and attack the Maratha left flank. Sited as they were facing south the Maratha artillery was unable to greatly hinder the British move but in its harassing fire did succeed in decapitating an orderly riding close to Wellesley as he crossed the ford.

Once safely over the Kaitna, Wellesley ordered his six battalions of infantry and supporting artillery into a line abreast facing west with his cavalry in reserve. Although it nearly halved his numbers, the EIC Madras Native Cavalry remained on the south bank to counter the Maratha Cavalry if they attempted to cross the Kaitna and guard the line of retreat should that become necessary. Wellesley knew that on this day only the iron nerves and cold steel of his superior infantry mattered. If they could not carry the field, nothing would.

As Wellesley completed these maneuvers and his army made ready to advance, Colonel Pohlmann realigned his three brigades in line abreast facing east, artillery to the immediate front. With his right flank anchored on the Kaitna and his left flank protected by the guns and garrison of Assaye, Pohlmann’s position was formidable. Wellesley was determined to come to grips with the enemy however, counting on the discipline and training of his British and Indian (Madras) troops to carry the day. Given the order to advance with fixed bayonets the infantry suffered grievously from grape, canister and round shot. Nevertheless they continued to close ranks and press on. At fifty yards they unleashed a volley of musket fire, charged and took their revenge on the Maratha gunners with cold steel. Once past the gun line the British and EIC infantry reformed and began to advance on the waiting Maratha line. Not all the Maratha artillerymen had been killed however, many had feigned death hiding under their cannons, nor had there been time to spike the guns. These men now brought their cannon about and poured shot and shell into the rear of the British and Madras forces. Observing triumph turn into disaster Wellesley personally led the 7th Madras Native Cavalry to retake the guns. This time none of the Maratha gunners were spared. No longer assailed front and rear the allied forces pushed forward into the teeth of Pohlmann’s line. Having witnessed the courage and discipline of the British and Indian infantry under fire, not to mention the destruction of 80 cannon with their attendant gun teams, the Maratha infantry broke. The first to flee were the European officers and sergeants, the rank and file hot on their heels, retreating northwards over the Juah. A formidable force remained in Assaye but rather than face the victorious and vengeful allied army they abandoned their position joining the retreat around 1800 (6PM). True to their bandit nature the Pindarries followed shortly thereafter. Months later Wellesley stormed the last remaining Maratha fortress at Gawilghur ending the Second Anglo-Maratha War thus ensuring England’s dominance of the Indian sub-continent. This campaign also secured his reputation as a battle tested commander who made the most of his resources and found ways to win no matter the situation or the odds. Even greater challenges would soon follow for Wellesley in Spain, Portugal and Belgium when Napoleon came to power in France and began to forge a continental empire.

Following the battle Wellesley informed Stevenson, “I should not like to see again such a loss as I sustained on the 23rd September, even if attended by such a gain.” Assaye was a costly albeit significant victory: 428 killed, 1138 wounded and 18 missing; a total of 1584 – over one third of those engaged in combat. Later in life Wellesley referred to the battle as “the bloodiest for the numbers that I ever saw.” And so it was, personally as well as professionally. Of the ten officers forming his staff, eight were wounded or had their horses killed. Wellesley himself lost two horses; one shot during the assault on Pohlmann’s right and his favorite charger, Diomed, speared as he led the charge to recapture the Maratha guns. During that desperate fight Wellesley was unhorsed and momentarily surrounded by the enemy. In his long military career it was his closest brush with death.

Following Waterloo, to avoid the carnage of another Napoleon aspiring to empire, the great nations of Europe convened the Congress of Vienna in September 1814. The Concert of Europe or Congress System it created ushered in 100 years of relative peace on the continent. Without Wellesley in command of the Allied Forces at Waterloo it is possible Napoleon might have emerged victorious in that pivotal battle. Almost certainly the nations of a war weary Europe would have rallied, as they had so many times before, to crush France and its Emperor. How long it would have taken to mobilize the forces to do so and what Europe would have looked like in the century following Napoleon’s ultimate defeat is a matter of conjecture. Thus the iron horse, the horseless carriage and Wellesley’s horse take us into the intriguing realm of Alternate History.

ENDNOTES:

(1) Franz Ferdinand was an advocate of increased federalism and favored tri-lateralism. Under this concept Austria-Hungary would have been reorganized by combining the Slavic lands within the Empire into a third crown. A Slavic kingdom would have eased tensions in that heterogeneous nation and served as a safeguard against Serbian irredentism. Consequently, the Archduke was seen as a threat by Serbian Nationalists. Indeed, Princip testified at his trial that preventing Franz Ferdinand’s planned reforms was one of the motivating factors in the assassination.

(2) After learning that the bombing attempt had failed Princip went to Schiller’s Delicatessen. When Princip came out later he saw Franz Ferdinand’s car reversing, having taken a wrong turn. The car then stalled giving Princip the opportunity to approach and shoot the Archduke and his wife at short range.

(3) Zangara has one other interesting claim to fame. When sentenced to death the state prison at Raiford had only a single “death cell” and it was already occupied. Since Florida law stipulated that convicted murderers must be incarcerated separately prior to execution prison officials were forced to add an additional cell. Hence, the term “death cell” became “death row.”

(4) At that time in England first sons of the wealthy inherited; the remainder had a choice of service in the church or service in the military. Service in the military, if successful, often lead to a career in politics. There were exceptions of course but as a general rule landed gentry did not go into the professions (law, medicine, etc.) and they certainly did not dirty their hands at business except as investors. Born the fifth son of Garrett Wesley, First Earl of Mornington, Arthur Wellesley chose a career in the army. Commissioned an Ensign in the 73RD Regiment of Foot on 07 March 1787 over the next twenty-eight years Wellesley served the British Empire with distinction in the Netherlands, India, Denmark, Portugal, Spain and Belgium. In 1793 Wellesley purchased a commission as a Lieutenant Colonel commanding the 33RD Regiment of Foot. Noted for bravery and coolness under fire during the siege of Seringapatam (05 April- 04 May 1799) during the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War against the Tipu Sultan, Wellesley truly came into the ascendant when his eldest brother, Richard Wellesley, Second Earl of Mornington, recently appointed Governor General of India, brevetted Arthur to Major General and gave him command of British and Indian Sepoy troops from the Madras Presidency in the Second Maratha War against Madhaji Scindia, one of the principal rulers of the Maratha Confederacy. This series of wars fomented by and undertaken on behalf of the East India Company would determine whether England or France would rule India.

(5) As an historian one must take care not to judge the past by current standards. That being said the British Army from 1700 – 1900 was a peculiar institution comprised of a confusing profusion of units with time-honored names reflecting its storied past: regulars, militia, fencibles, associations, volunteers, yeomanry, rangers, local militia and provisional cavalry. Despite the wide variety of designations, enlisted men generally entered service in one of three manners. Recruitment parties and press gangs were used to fill the ranks of the regular army. Per the Militia Act of 1757, militia units were raised by ballot and roughly similar to our modern National Guard, part-time forces, called volunteers, formed the third element of the army. Daily life in a military encampment was dirty, pay was low, food was poor, order was strict, discipline was rigid, punishment (which included running the gauntlet, branding and flogging for even minor infractions) was harsh and disease was a greater threat to health than battle. The army provided very little beyond the basic necessities creating a shadow army of sutlers and camp followers who trailed the army everywhere it deployed. In spite of all that there was no shortage of men for depressed economic conditions in the large urban areas and a lack of opportunity in remote rural areas made army life attractive in comparison. Many officers came from the militia; a small number were gentlemen volunteers who served as soldiers but messed with officers until vacancies became available. Commissions could also be purchased by those who could afford them. The status conferred upon becoming an “officer and a gentleman” not to mention, improved future prospects, enticed many men to incur the considerable expense of acquiring a commission and the even greater cost of maintaining the horses, uniforms, field gear, etc., expected of a proper gentlemen. The final path to officer status was battlefield commissions for acts of extraordinary bravery. Although not unheard of, these promotions were infrequent. The result was a mixed bag in leadership ranging from incompetent to brilliant. Fortunately for the Empire career sergeants made the system work just as their counterparts, the Centurions, backbone of the Imperial Legions, made the Roman army successful. For all its eccentricities the British army was highly effective achieving results far out of proportion to its numbers.

(6) Organized into three brigades, these were the best trained and most disciplined troops of the Maratha (Mahratta) army thanks to a cadre of mercenary officers and non commissioned officers. Colonel Anthony Pohlmann, a Hanoverian, former sergeant in EIC employ and deserter, commanded the largest brigade comprised of eight battalions. Colonel Jean Saleur, a Frenchman, commanded another brigade consisting of five battalions. Finally, Major John James DuPont, a Dutchman, led a small brigade of four battalions. It was not unusual to find European and even American soldiers of fortune in service to the Maratha Confederacy. Recognizing that only European style soldiers could stand against the highly professional British army the Maratha paid handsomely and offered greater opportunities for advancement, far better indeed than the EIC, for veterans with proven martial skills. Former Sergeant, now Colonel Pohlmann was a case in point. Although the troops were paid and supplied by Daulat Scinda overall command in combat during battle fell to Colonel Pohlmann.

(7) Order of Battle: HM 19th Light Dragoons, HM 74th Highland Regiment of Foot, HM 78th Highland regiment of Foot (The Ross-Shire Buffs), 4th EIC Madras Native Cavalry, 5th EIC Madras Native Cavalry, 7th EIC Madras Native Cavalry and one battalion each from the 4th EIC Madras Native Infantry, 8th Madras Native Infantry, 10th Madras Native Infantry and 12th Madras Native Infantry.

(8) Colonel Stevenson did march to the sound of the guns however a devious native guide, whom the Colonel later hanged as a spy, led Stevenson’s column astray. Thus the supporting force did not arrive in time to take part in the battle of Assaye. Since Wellesley’s force had been rendered temporarily combat ineffective and needed time to recover, it did play a major role in the pursuit of the broken Maratha army. In the months that followed Assaye, the rout at Argaon and the storming of the fortress of Gawilghur which forced Scindia and Berar to sue for peace ended the Second Anglo-Maratha War.